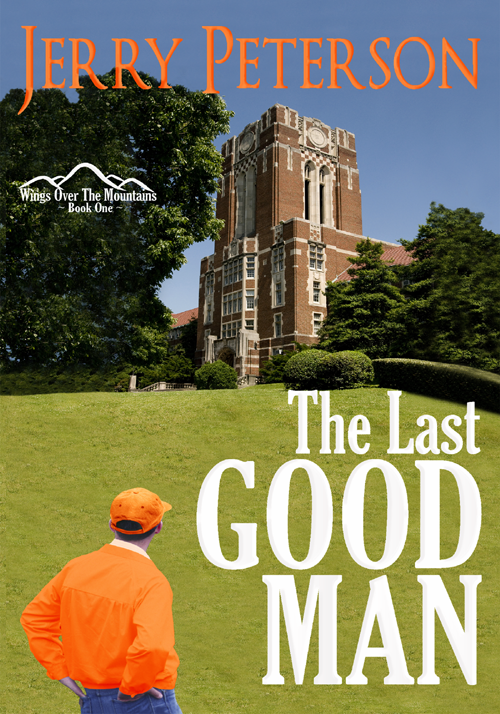

Back to school

It was while I was a graduate student at the University of Tennessee that the idea for this novel began to churn around . . . a 65-year-old guy decides to sell his business to his son and retire. To do what? To fish. Well, to fish and drink beer because retirement is boring.

He becomes a falling-down drunk, as he was when he was a young man home from World War II.

It's his granddaughter who saves him by telling him you've always wanted to go to college. Now's your chance. Come up to UT with me.

The first three chapters of the manuscript told all this.

Good writing. Rich writing.

And I cut them . . . because the story really starts on the first day, when Pappy is registering for classes. Chapter 4 . . . now the new chapter 1.

Here's the novel in a paragraph: Pappy Brown, at age 65, finds himself going to college, a freshman no less. His is a story of life changes, wild times on Greek Row, and late romance, with a dash of Christmas adventure thrown in. For a Christmas gift, Pappy–the last good man–must find the father of a boy whom he has befriended, the father, a Vietnam vet running from his demons.

So here's chapter 1.

Big damn place

Pappy Brown pored over the printout of his classes, the classes that were about to take a shark-sized bite out of his bank account.

“Gawd, ya could sure stack a lot of hay in here, couldn’t ya?” someone behind him said.

Pappy twisted around. There stood a tall, gawky kid with no chin and an Adam’s apple the size of a small boy’s fist. The youth gazed up, gape-mouthed, into the superstructure of the University of Tennessee’s arena high above the basketball court where several thousand students had cued up to pay their fees, the buzz of their multiple conversations sounding like bees mumbling around a hive.

The kid swivelled his head, as if he were measuring by eye the length of the arena. “This is absolutely one humongous place.”

“You from the farm?” Pappy asked.

The youth brought his gaze down to meet Brown’s. “Yeah, James Dempsey, freshman. From Bucksnort.”

“First time here, huh?”

“You got that right”

Pappy extended his hand. “Willie Joe Brown, Maryville. I’m a freshman, too, the world’s oldest.”

Dempsey stared at him. “Really?” he said as he shook Brown’s hand.

“Coming on sixty-five. I could be your grampaw.”

“I guess you could.”

The lines moved. The two shuffled forward, Brown in his plumber’s twills, Dempsey in cutoffs and a T-shirt that read ‘Aggies do it in the cornfield.’

“You got a major picked out, James?”

“Junior. Call me Junior. James is my dad. Agriculture engineering. How about you?”

“Not the damnedest idea.”

“Why’s that?”

“Well, I’ll tell ya, Junior, I did something stupid. I sold my business, and then discovered I didn’t have nothing to do anymore other than fish and drink beer. And that made my granddaughter mad. She insisted–insisted–I find something better to do.”

“Take some classes?”

“‘College,’ she said, ‘Grandpops, you always wanted to do that.’ I guess I did, so here I am.”

“That’s some story.”

“Isn’t it, though? So you’re goin’ for ag engineering, I bet that’s a load of tough classes.”

“Oh, I’ve got a three point nine-seven through four years of high school. I think I can handle it.”

“Hate to remember what I got in high school. Of course, that was back when Thomas Edison was still trying to invent the light bulb.”

Dempsey’s eyes widened.

“I’m pullin’ your leg,” Pappy said.

“If you didn’t have the grades, how’d you get in?”

“Somebody took pity on an old duffer.”

“You’re puttin’ me on.”

“No, they gave me points for my time in the Army.”

“My great-uncle was in the Army. My dad was Navy.”

“Next, please.”

A new voice. Pappy turned to it and discovered two things: the voice belonged to a pleasant-looking woman in a blue blazer with a University of Tennessee crest on the breast pocket, and there was a hint of rose water about her, a contrast to the smell of sweat that permeated the arena. Pappy handed his papers on. “William Joseph Brown Junior,” he said. He winked at Dempsey when he said ‘Junior.’

The woman read down the printout. “Everything looks to be in order. Are you changing any classes?”

“No, ma’am.” Pappy took in her name badge, then added, “Bernice.”

“It’s Missus Lippmann to you.”

“Pardon?”

“My name is Missus Lippmann. I work in the Registrar’s Office. If you should have any problems with your classes in the first three weeks, I want you to come see me.”

“I guess I can certainly do that.”

“How are you paying? Cash, check, credit card? Are you on scholarship?”

“Oh gosh no, no scholarship. A check.”

“I should warn you, if your check has the least bit of rubber in it, I will send the campus patrol to have a chat with you.”

Missus Lippmann smiled.

Is she joshing? Brown took out his checkbook. He opened it on the table and bent down to write. “This sure is a lot of money.”

“Yes, and I appreciate every dollar of it. This is my house payment for the next several months.”

“You get it?”

“You don’t think I give these checks over to the university, do you?”

“Ah-ha. Do I get a money-back guarantee on my classes?”

“You’ll have to talk to the president about that.”

“Our former governor?”

“Lamar Alexander, that’s right.”

“I can do that, see, I did the plumbing at his momma’s house.”

“In Maryville?”

“That’s right.”

“You’re a plumber, then?”

“I was. I sold my business to my son, so now here I am, a spankin’-new student at big UT.” Brown tore out his check. He handed it to the registrar clerk.

She stamped PAID on his class schedule and on the duplicate which she kept. “Your check will be your receipt. If I don’t see you sooner, I’ll see you back here at the beginning of the spring semester.”

Brown nodded. He turned away to find Dempsey waiting on him.

“My bank account’s considerably lighter,” Pappy said.

“My dad’s, too.”

“You been by the bookstore yet?”

“That’s my next stop.”

“Well, what say we go together?”

“Fine by me.”

Pappy and Dempsey hiked up the bleachers toward the exit. Before they got half way, someone called out, “Grandpops!”

He swung back.

A young woman waved to Pappy from below, in the pay-tuition line.

He returned the wave. “I mentioned my granddaughter,” he said to Dempsey, “that’s her. Come on, I’ll introduce you.”

Pappy trotted back down the bleachers to the floor. There he elbowed his way through a claque of students, his fellow freshman close in his wake. “Hang with me, boy. You’re about to meet the greatest twenty-one-year-old gal of your life.”

“Hey, watch it, old man,” someone barked.

Pappy stopped. He pivoted and stared up into the glowering face of a thick-set student some eight inches taller and one-hundred fifty pounds heavier than he.

Dempsey pushed in. “Sorry,” he said to the other student and hustled Pappy on.

Brown twisted back. “I can hold my own.”

“I don’t think so. Do you who that is?”

“No and I don’t give a damn. He called me an old man.”

“You are.”

“Well, I’m not that old.”

“That’s Bo Smith. Mean as they come.”

“Right tackle for the Vols?”

“That’s him.”

“Junior, this time I do give a damn. Thanks.”

Pappy and Dempsey continued on until they broke through the last knot of students that separated them from Pappy’s granddaughter and the cluster of young women with her.

“Caroline,” Pappy called out.

Caroline Brown gave a head jerk in the direction from which Pappy and Dempsey had come. “What was that all about?”

“Guess I stepped on that fella’s foot back there. Junior thought he was going to pound me into the floor for it.”

She shifted her backpack. “I’m sorry I stood you up, Grandpops. There was business at the sorority. Everybody, this is my grandpops. Be nice to him. He’s the new kid here, a freshman.”

“Hi,” said one of the girls in the line near Caroline. “I’m Beth.”

“I’m Sandra.” That introduction came from a beefy brunette whose smile, Pappy thought, could melt an ice sculpture at a wedding reception.

“I’m Ellie,” said a blond cheerleader-type. She gave Pappy’s hand a playful pat. “Ellie Esther Emma Easterling.”

He patted her hand in return. “I’ll bet your pop had fun coming up with that name. Friend of mine, when I was your age, was Karen Kathleen Kelley Katz. We called her Kitty.”

“Oh, that’s clever.”

“It’s true.”

“Well, Ellie is my mom’s name. Esther comes from a great aunt. Emma was my grandmother on my mother’s side, and Easterling I inherited from Daddy.”

“Ellie, that’s a proud name.” Pappy hauled Dempsey in. “I’d like you all to meet James Junior Dempsey, a tall drink of water from Bucksnort, Tennessee.”

Puzzlement nudged an eyebrow up on Easterling’s forehead. “I don’t think I’ve heard of that.”

Dempsey gave a one-shouldered shrug. “It’s between Nashville and Memphis.”

“Me, I’m from Goodno, Florida, way out in the swamps of the Everglades.”

Pappy grinned. “I’ve done a little fishing in the Gulf off Naples.”

“Naples, yes, Goodno’s inland from there, about fifty miles.”

“So, Ellie, why are you way up here rather than down at, say, Florida State?”

“My daddy. He’s a UT graduate, Nineteen Sixty-One. Met my momma here.”

“Ahh.”

“They said this is the only place they’d ever let me go to college.” Easterling patted Pappy’s hand again. “Your Carrie kinda looks after me. We’re in a lot of the same classes and the Theta Delts.”

Sandra squeezed into the conversation. “Mister Brown, did you know we elected Caroline our president last night?”

Pappy turned to his granddaughter. He made a flourish with his hand and knelt before her. “Madam President.”

“Isn’t he the cutest?” Easterling said to the others, giggling.

“Grandpops, come on, you’re embarrassing me.”

Pappy pushed himself up. He took Caroline’s hands in his. “I’m proud of you, Carrie girl.”

“Caroline, move up,” another girl said. “The line’s moving.”

Pappy let go of her hand. “You better go along. Junior and I, we’re on the way to the bookstore. We gotta buy us a pile of books so we can do us some larnin’ at this hyar university.”

Another giggle rippled out of Easterling. “Oh, you’re really cute, Mister Brown.”

“Call me Pappy.” He pointed to the name stitched above his shirt pocket as he backed away.

“Get used books,” Caroline called over the crowd. “You’ll save money.”

“After what I left at the pay window, I need to do that.”

“You’ll come over for supper?”

“To your sorority house? You’ll let a man in?”

“I’m the president now. I can do that.”

“How about Junior?”

“Sorry. But he’s invited to our first kegger.”

Pappy slapped his forehead. “I’m shocked, Caroline, shocked. You drink in that place?”

“Grandpops.”

“What time?”

“Six. Sharp.”

He waved, then he and Dempsey plowed away through the mass of students waiting to pay their tuition and fees. “Your grandfather’s cute as a button,” they heard Sandra say. “Can I take him home to Goose Horn?”

Dempsey shook his head. “Pappy, you sure cut a swath with the girls.”

“That’s me, a devil on wheels.”

“You got a wife, don’t you? What’s she say about this?”

“Very little.”

“Why’s that?”

“She’s a resident at the Our Savior Baptist Cemetery.”

“I’m sorry.”

“Don’t be. It’s been nineteen years.” Pappy, with Dempsey soldiering beside him, clipped up the steps toward the second-level exit. “We each only get so much time on this old earth, so we got us a duty to enjoy it.”

“My dad would like knowing you.”

“Junior, if he’s a wide-eyed wonder like you, I look forward to meeting him. Tell your folks to come up for Homecoming.”